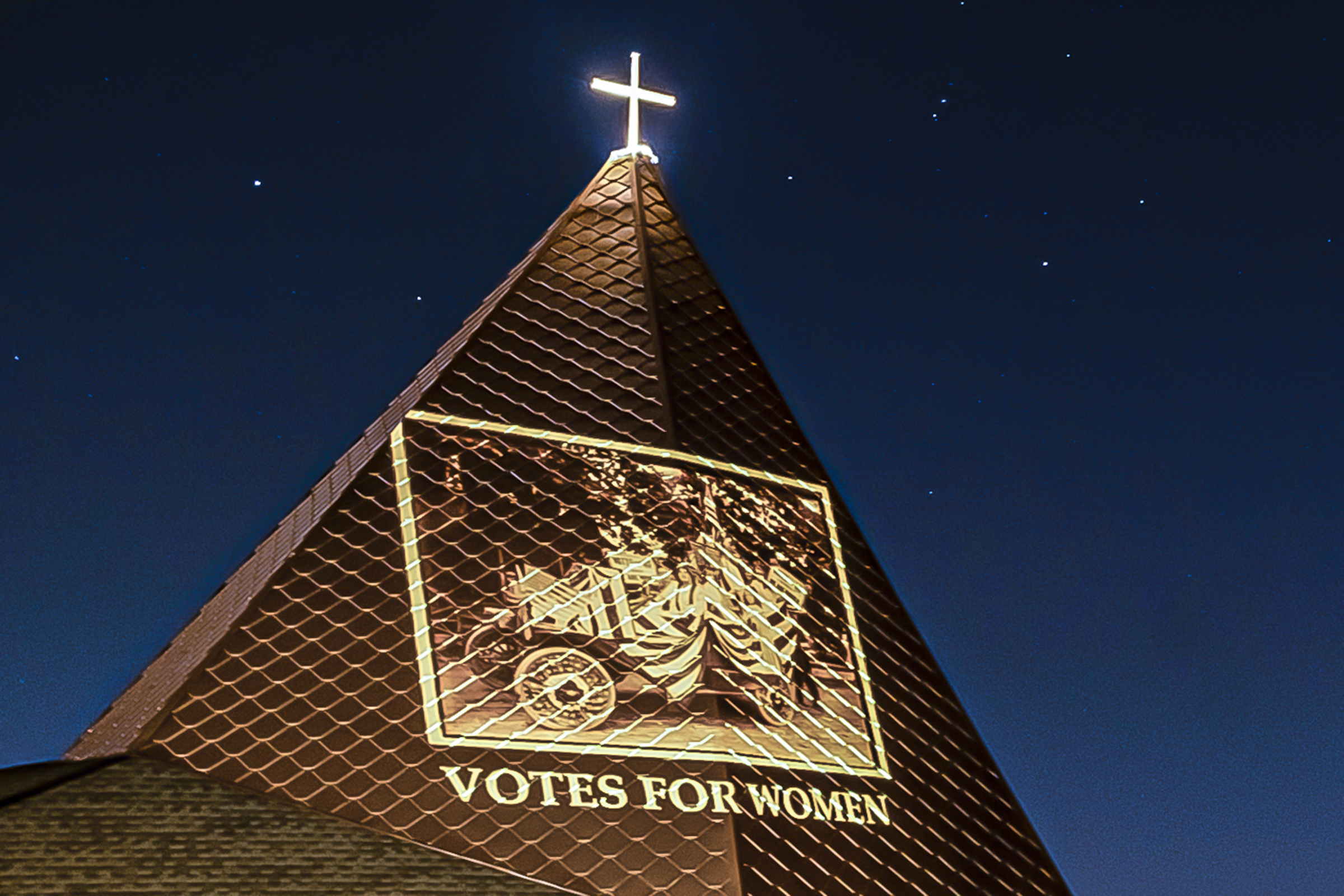

Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church,

Hester Jeffrey & Susan B. Anthony

Nicole Doughty on Hester Jeffrey

Hester C. Jeffrey was born in 1842 to free black parents in Norfolk, Virginia. In her youth, she received a quality education, and many considered her a talented musician. As a young adult, she lived with her family in Boston, Massachusetts, before relocating to Rochester with her husband in 1891. Jeffrey’s impact on the area’s abolitionist and women’s suffrage movements was significant. Although overlooked historically due to the racial character of the women’s suffrage movement and the absence of a recorded legacy, Jeffrey’s vibrant life of activism reveals a black woman who broke free, wielded political agency, and made significant advances for herself and those around her. For example, in 1902, she founded Rochester’s Susan B. Anthony Club for black women. Jeffrey’s ability to promote solidarity and relationship building across political and racial lines made her especially effective in bringing together black and white women in the suffragist movement and other organizations. In the late 1920s, Jeffrey moved back to Boston and died surrounded by family and loved ones in 1934. Today, she is resting in an unmarked grave in Everett, Massachusetts, leaving behind a powerful legacy of political and social activism advocating universal social justice and human rights.

By founding and participating in various organizations working toward political and social goals throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, Jeffrey made essential contributions to Rochester’s activist history. Her Hester C. Jeffrey’s Club encouraged young girls to pursue higher education and awarded scholarships to the now Rochester Institute of Technology. She started The Climbers to help the elderly and needy while supporting three young girls living in a southern orphanage. Her Susan B. Anthony Club facilitated dialogue between suffragists and provided public goods for mothers with young children through its Mother’s Council. Jeffrey also served as National Organizer for the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (now the Federated Women’s Clubs) for four years, and later as president of the New York State Federation, making her a very accomplished woman by any standard.

Notably, Jeffrey often became involved in groups traditionally thought of as predominantly “white” organizations, such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Despite the permeating racism of the time, which had begun to infect the women’s suffrage movement, Jeffrey did not hesitate to pursue the goals of universal suffrage and natural human rights. She formed strong political activist networks throughout New York along the way. While overshadowed by a friend and fellow suffragist Susan B. Anthony in the historical record, recent investigations into Jeffrey’s life have challenged outdated assumptions about black female participation in political life at the time. Her fearless pursuit of universal emancipation despite living during a time filled with blatant racism and sexism shows the power of her convictions for equality and freedom. Further, Jeffrey’s political involvement was dynamic, working to uplift many different communities at once through community organizing, charitable contributions, and political reform advocacy.

Jeffrey lived her life in such a way that gender, class, and racial barriers melted away whenever she entered a space. Her diverse group of friends and activist interests evidence a high degree of cooperation and tolerance necessary for her to work towards universal equality in a divisive and discriminatory time. A lesson we can take from her life is that we should view each other as equals and treat all human beings with dignity and care, regardless of demographics or identity. Her tenacity as an activist was essential to her success as an organizer; she befriended and worked alongside elite white suffragists like Anthony while also serving the needs of the elderly and poor and cultivating relationships with those she helped. Anyone interested in continuing Jeffrey’s legacy can incorporate these lessons into their lives to advance equality and freedom through inclusive community building here in Rochester.

Marisol Morales on Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, to Quaker parents in Adams, Massachusetts. Per the Quaker tradition, she began receiving education from an early age. In 1845, Anthony moved to Rochester, and in 1846, began teaching at Canajoharie Academy. Her abolitionist and women’s rights work began in the 1850s when she met, among others, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Anthony and Stanton would continue to work closely over the years in the fight for women’s suffrage. Conflict over the Fifteenth Amendment led to a split between suffragists, and Anthony eventually formed the National Woman Suffrage Association with Stanton in 1869. She famously voted in the 1872 presidential election in Rochester, leading to her arrest. When tried, her all-male jury ordered her to pay a $100 fine. She never paid the fine. Anthony continued to give speeches even after retirement and died in 1906, in her Rochester home on Madison Street, before the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage. Anthony’s resting place is in Rochester’s Mt. Hope Cemetery.

Anthony questioned the validity and legitimacy of a democracy that does not allow all citizens to vote. She makes clear through her speeches that she believed that the Constitution already guaranteed the right to vote to every citizen. For Anthony, living in a democracy that does not allow groups of citizens to vote is no different than living in a monarchy. Therefore, she never paid the fine received for voting in the 1872 election. She believed that she did not commit a crime. In light of her example, we would be remiss not to discuss modern-day disenfranchisement and voter suppression. While the 2020 presidential election brought us conspiracies about the efficacy of mail-in voting, active suppression of the vote has been happening since our nation’s birth. 19th and 20th Jim Crow laws prevented voting. Today, voter ID laws and lack of access to polling places, among other things, make voting more difficult. Voter suppression disproportionately affects minority communities compared to white communities. While the pretense of protecting against fraud often justifies new laws, the data reveal limited voter fraud instances. While we can only speculate about what Susan B. Anthony would have thought about discouraging the expansion of the vote; we can take a page out of her book and ask ourselves if laws that disenfranchise or suppress voters are consistent with the vision of a free and democratic nation put forth by the Constitution’s framers.

While being integral in the fight for voting rights, the women’s suffrage movement was very white. It was not that there were not Black suffragists; rather the movement often excluded Black Americans. Like Susan B. Anthony, many white suffragists got their start in abolition, but a current of racism ran through the women’s suffrage movement. Anthony opposed the Fifteenth Amendment’s passage because it gave Black men the right to vote before women. When the Nineteenth Amendment was up for ratification, some white suffragists argued its passage supported white supremacy. The lesson taken from this is that our fight for civil rights needs to be intersectional. The world is a complicated place. Our backgrounds and identities influence how we interact with the world. The experience of a white woman will never be the same as that of a Black woman. This means white women face different issues than Black women, despite both being women. Race, gender, class, sexuality, nationality: intersectionality asks us to meet our differences to fight for change that addresses more than the white experience.

Another aspect of the suffragist movement rarely discussed is its queerness. The historical record describes some suffragists as lesbian, including Susan B. Anthony. Letters she exchanged with women like Anna Dickinson and Emily Gross paint a picture of intensely romantic relationships. Anthony’s lack of a male partner connected to her politics. Having a husband and children would have been a liability, something she confirmed whenever a fellow suffragist married. Non-queer historians often sweep away evidence of historical figures’ queerness. To recognize the queer nature of history is to embrace the queer community of today.

So many things have changed since Susan B. Anthony lived, but her ideas about democracy still hold. A state that refuses to acknowledge the rights of its people is not genuinely democratic. We must apply this logic to modern voter suppression and all social injustices that this country’s different peoples face.

Bibliography & Further Readings