Geva Theatre Center &

Emma Goldman

Ruth Dalton on Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was born on June 27, 1869, to a family of Jewish descent in modern-day Lithuania. At age 16, Goldman emigrated to the United States with her older sister to escape abuse at the hands of family and authorities. In 1886, Goldman moved to Rochester, where she would live for only three years before moving to New York City. Her radical political views took shape during her time in Rochester and later New York City, where she enjoyed Johann Most’s mentorship. Goldman died on May 14, 1940, in Toronto, Canada. With Goldman’s body returned to the United States, she rests in Forest Park, Illinois, near those executed for their roles in the Haymarket Affair.

From a young age, Goldman suffered abuse inflicted by her father and Russian and German authorities. Hoping to flee hard-labor conditions and abuse, Goldman departed with her sister for America, dreaming of a better life. After arriving in Rochester, Goldman’s dreams of a better life evaporated. Goldman found better working conditions in Rochester, but the hours were long, the pay worse, and the workplace stricter. During her stay in Rochester, Goldman developed sympathy for communist and anarchist movements and despised authority figures. However, following Chicago’s Haymarket Affair, Goldman could no longer remain silent. She moved to New York City to fight for political change in America. “The political arena leaves one no alternative, one must either be a dunce or a rogue.”

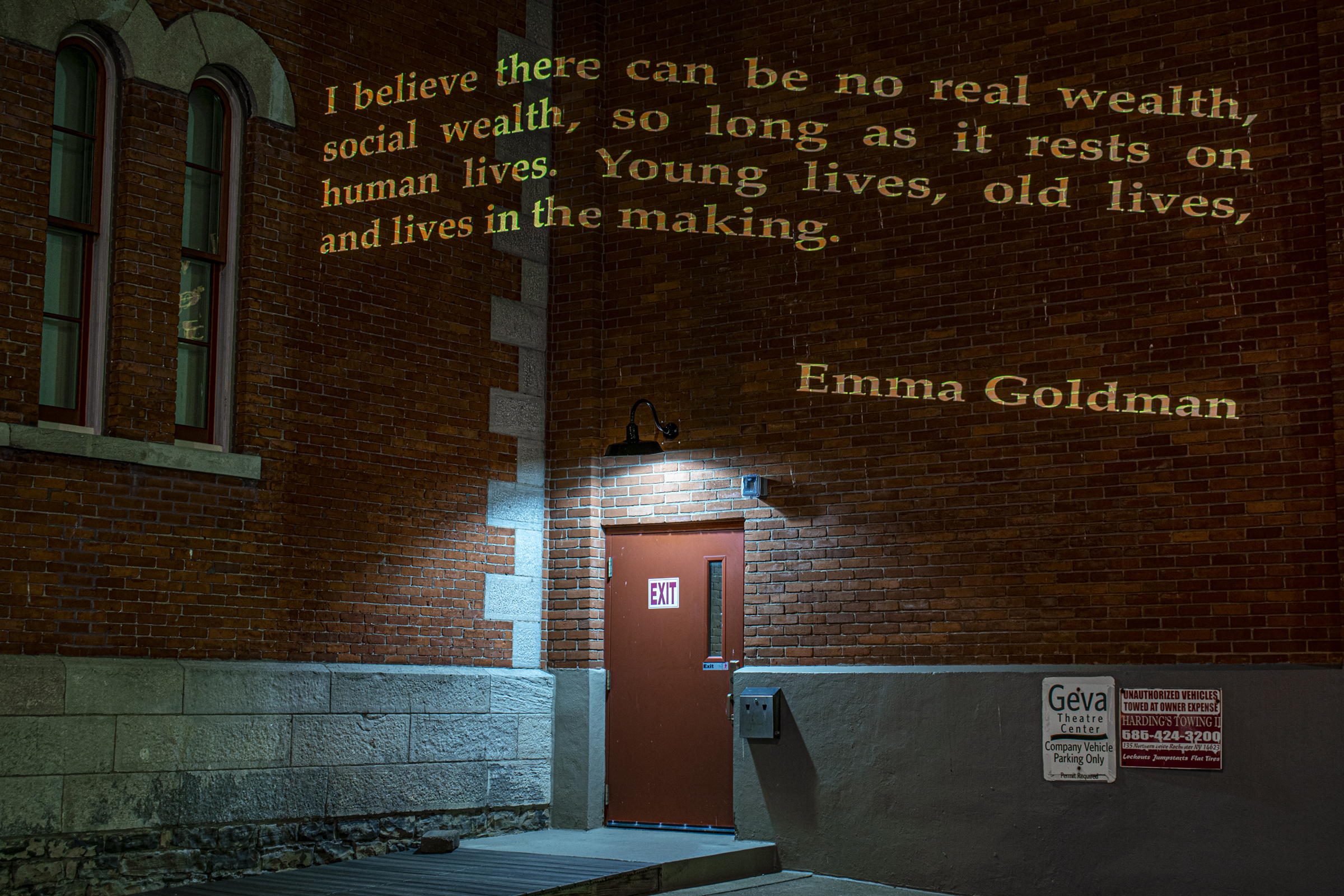

After moving to New York City, Goldman became a protégé of prominent German-American anarchist thinker Johann Most. Under his guidance, Goldman became a student of anarchist political philosophy and a great orator. During her time as Most’s protégé, she also became influenced by Russian anarchist thinker Alexander Berkman. Together, they toured America, denounced authority, and called for working-class emancipation by revolting against controlling powers to bring about justice, freedom, and equality. Goldman worked hard to recruit fellow workers to revolt against what she saw as the repressive class. She especially called for women to separate themselves from the patriarchy. She fought to change the social structure that restricted women. This contrasted with feminists who called for women to change their lives within the existing system individually. “It is Morality, which condemns woman to the position of a celibate, a prostitute, or a reckless, incessant breeder of hapless children… Religion and morality are a much better whip to keep people in submission than even the club and the gun.” While some considered Goldman to be one of the most dangerous women in America and nicknamed her “Red Emma,” she was one of the most influential women of her time. She was an anarchist agitator, labor activist, free speech activist, birth control advocate, and a free love feminist.

While Goldman was an influential anarchist thinker and feminist, she often clashed with her anarchist and feminist peers. Often Goldman was too radical for her fellow feminists and anarchists and would blame women and laborers for their harsh conditions. Goldman stuck to her beliefs regardless of the damage to her image among fellow radicals. Goldman greatly emphasized freedom and equality for women and workers no matter the cost. “‘I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things.’ Anarchism meant that to me, and I would live it in spite of the whole world – prisons, persecution, everything. Yes, even in spite of the condemnation of my own closest comrades I would live my beautiful ideal.”

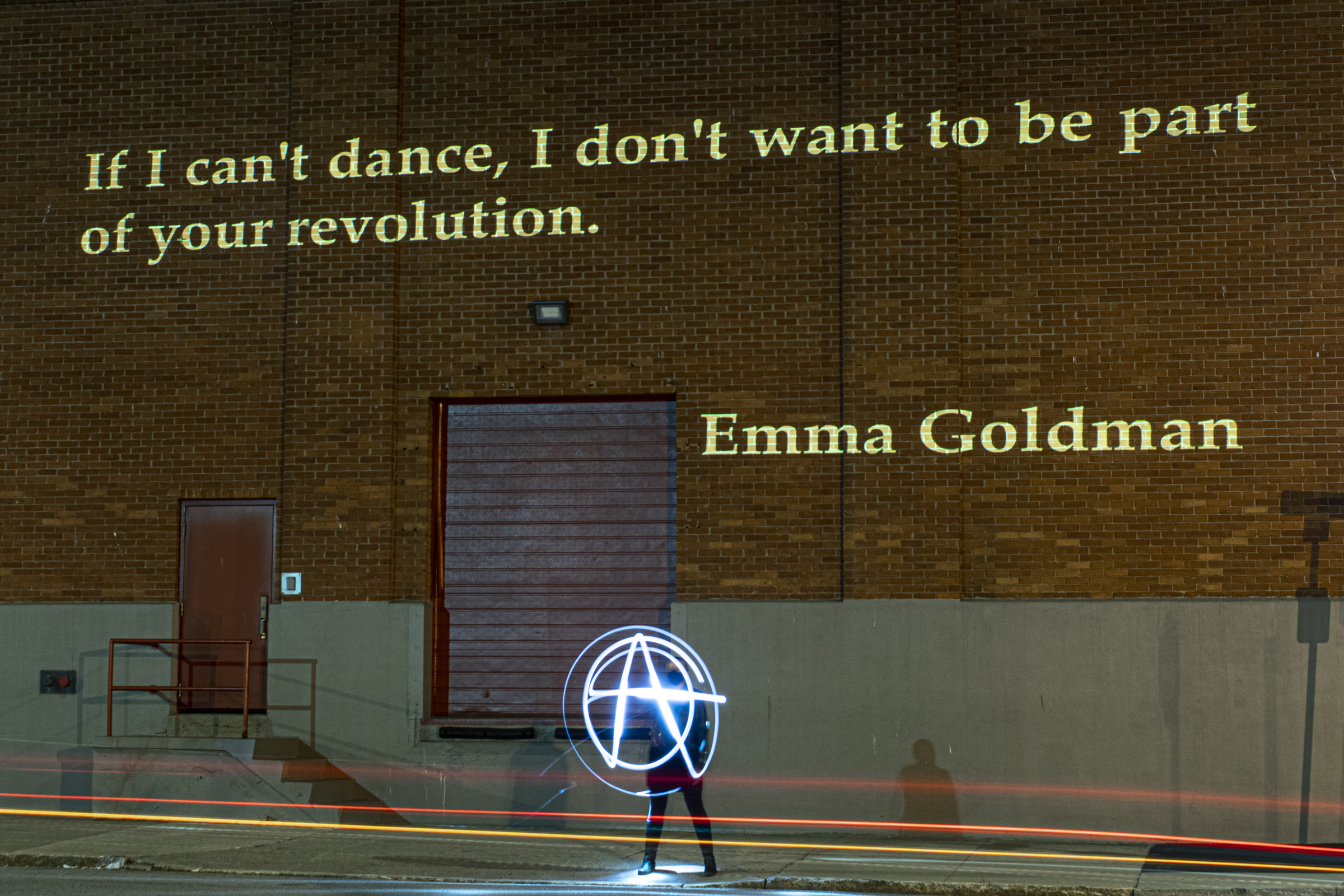

While Goldman was a champion of freedom and equality, her ideals were often harsh and unrealistic. During her life, Goldman supported or associated with acts of political violence. Goldman faced arrest, imprisonment, and eventually deportation from the United States. We must weigh this part of Goldman’s legacy alongside her belief in justice, freedom, and equality. She often envisioned a world of freedom and equality while only critiquing her present conditions and revolutionaries and offering no solutions. Although not a direct quote, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution,” is a sentiment attributed to Goldman. My question to the readers is this: After years of political polarization and turmoil, including during a pandemic, how do you view Goldman’s critiques? While her visions of absolute freedom and equality seem like an unattainable utopia, do you feel any truth in them? Do you believe that we can ever achieve the right to dance during a revolution?

Bibliography & Further Readings

Previous: Corinthian Hall Site & Frederick Douglass

Next: Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church, Hester Jeffrey & Susan B. Anthony